“It can be said that the history of modern art (in particular) is the history–retold and repeated—of the internal architecture of the work, seen simultaneously as container and content. Nevertheless, the work of art only exists, and can be seen, in the context of the museum/gallery that surrounds it, for which it is destined, and to which, notwithstanding, very little attention is given”. Daniel Buran

As developed by the French artist Daniel Buren in his well-known text on the relation between work of art and the space which contains it 1/, it can be affirmed that, at least since the renaissance, the work of art possesses an “internal architecture”, which has had its own and autonomous development, which gradually has removed it from that other architecture that contains the work of art, the site in which the work of art is seen. The concept of the specificity of the site, appears during the seventies, as an evolution of the minimalist artistic practices, which, as noted by Douglas Crimp, “would redirect the conscience [of the spectator] to themselves and to the conditions of the real world that establish contact with reality. In such a matter, the perception coordinates were established as existing not only between the spectator and the work of art, but between the spectator, the work of art and the space inhabited by both”. 2/ This indissoluble relation between a work of art and a given space (and in some moments also precise) is the basis for the concept of the installation, that we could define as that condition of the work of art in which the relation with the space in which it is exhibited, is intrinsic to its own enunciation as a work of art; the support (physical and institutional) which can’t be renounced in vain in a given situation and moment for any work—it is exacerbated her.

Buren argues that a “work of art and space must implicate themselves mutually”. Therefore two important conclusions can be inferred. On the one hand the work of art implies the support of the space in physical terms, it becomes part of it, it integrates with it–¿where is the packaging of Pont Neuf left without the sheets, and Christo´s action?; On the other hand, the space, its context—cultural, social, political– has a direct implication in the sense and the conformation of the work of art. Of course, this denies the possibility of a neutral space in art. The paradigm of the white cube, whose archetype is established in the thirties with the Museum of Modern Art of New York, and that is consolidated with the reconverted industrial spaces of the seventies´ New York scene, hides—behind its appearance of neutrality—the impossibility of a space that is not “charged”. All contemporary artistic practice is conscious of the strong presence of the space in an exhibition. Some works of art go beyond, and not only are integrated physically with the space, but reflect on it. The work of Beatriz Olano forms part of this tautological practice in which, that which is architectonic, is at the same time, container and content of the work of art.

From the very beginning of her artistic career, Beatriz Olano has implicated the space in her works of art, which is more precise than to refer to them as “installations”. In Wallpaper, one of her first works of art, she appeals to a series of architectonic planes that had been worked not as representations of real spaces, but rather as autonomous compositions—thus negating the inherent function of the architectonic plane—and with these bidimensional compositions intervenes the totality of the interior surfaces of an enclosure. This first experience is enriched by more recent works of art in which she incorporates elements of the “real” world as she appropriates the space, with which her three-dimensional abstract compositions begin to function in an allegorical manner, alluding to the diverse spaces of the architecture based on the materials, the colors and the textures: the artificial flower and grass are signs of nature; the felt and the foam suggest intimate spaces; the wallpaper remits us to precise cultural and temporal contexts. The utilization of furniture, recycled windows and doors, involves the presence of architecture itself as a tautological sign: the work of art speaks of space in space, of architecture reconfiguring it with its own typological elements.

Never is this reflection clearer than in Visibilidad, a work of art presented in the “New Names” exhibit at the Luis Angel Arango Library in 1998. Olano disposed of the floor in a great plane realized with mud tiles—in reference to popular architecture—and opposed to this evoking presence the curved wall of the room, revealing, by opposition, the rational character of the space and making visible, by this contrast, that the building is one of the most flagrant examples of modern architecture, that, in the sixties leveled Bogota’s Historic Downtown District, constituting itself in an interesting institutional criticism to the context in which the work of art was presented. Visibility towards a part of an artshow that explicitly addressed “painting” 3/; with their materials (the surface of the tiles and the photography of a sky projected unto the wall), Olano´s work ironically responded to the representative function secularly associated to painting, and to its virtual invisibility in the contemporary artistic context.

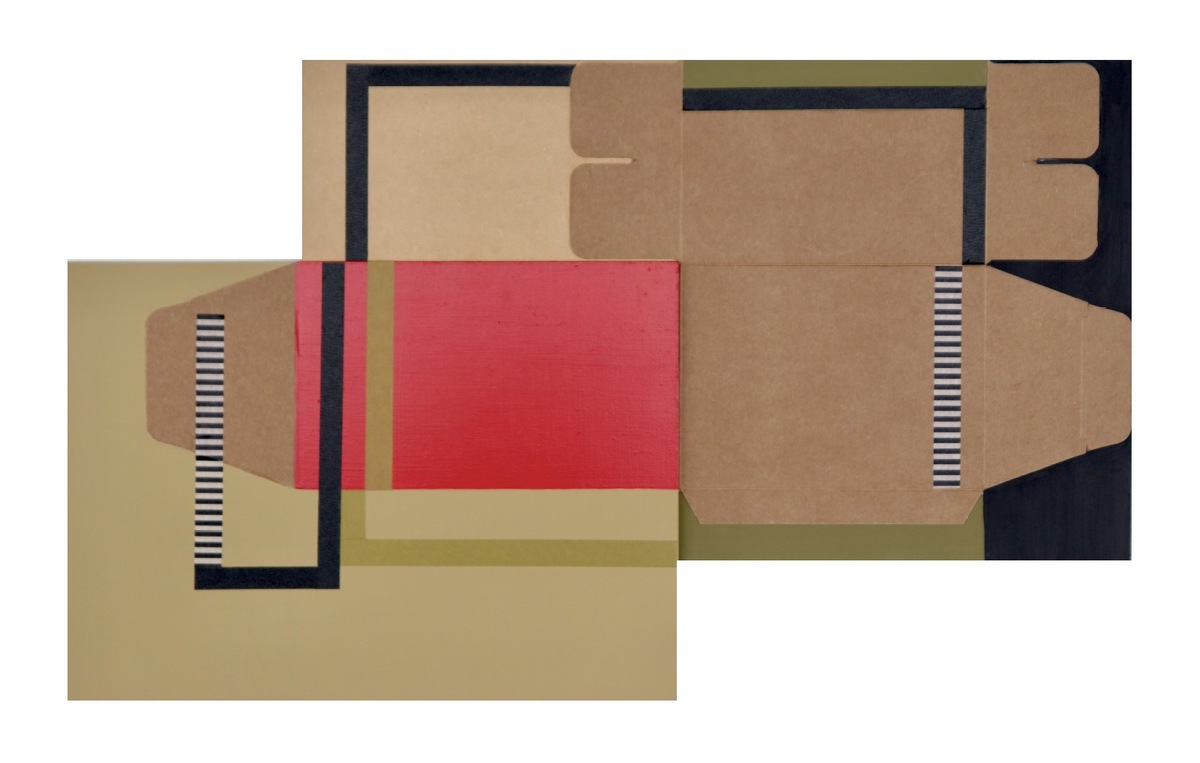

Although it can be affirmed that there has always been a theme in Olano´s work (the space), this is obstinately centered in itself. But, in some of the works of art, one can see a relation, from architecture, with a theme that is almost a signature of Colombian art in the 1990s: death. In Olano´s work, these theme appears in the form of abstract references to mortuary architecture: crypts, memorial stones and other elements of the visual vocabulary of cemeteries. This is the case of Empaques (work presented to the Johnnie Walker prize in 1999) that consisted in the disposition, in a wall, of paper bags colored with red, that, when organized in regular rows evoked mortuary crypts, as well as the reference to the memorial stones and the use of artificial flowers in Jardines, a work presented to the 2000 Regional Salon. The recent exhibit Del más acá continues with this reference to death, from the compositional rigor that characterizes Olano´s work, and gathers several of the formal metaphors that are its own: the plastic flowers, the lines that cross the room diagonally, and that flow in the perception of the spatial references (such as the orthogonality of the space); the systematic and orderly disposition of the floor and wall objects; the use of slide projections through which reality is introduced based on the character of index inherent to photography.

Jose Roca, 2001

Notes:

- Daniel Buren, “Function of Architecture”, in Thinking About Exhibitions; Routledge, London, 1996, p. 313

- Douglas Crimp, On the Museum´s Ruins; MIT Press. Cambridge, 1993, p154

- In fact, the last collective exhibits in which Olano has participated, refer explicitly to paintings in its curatorial parameters. The one exhibit, already referred to and named “Aproximaciones a los Pictorico”, took place in the Luis Angel Arango Library in Bogota, in 1998; A second exhibit, “Colombian Painting in the 1990s”, at the Museum of Modern Art in Cartagena, also in 1998, and “Todos Pintura” in the Sala Suramericana in 1999.

Exhibitions, projects and participation in art fairs with the gallery

Kevin Simón Mancera I Beatriz OlanoStage Bregenz

Luxembourg Art Week 2023

HÖHENFLUG IN DER KRISTIANIA GARAGE WINTER 2023/24

Summer Gallery Salzburg 2023